If you want to optimise your recovery from a hard workout, you need to watch the levels of stress in your daily life. So says the latest research out of the Yale Stress Centre this month. You might use your workout as an outlet for the stresses and strains that you experience in your daily life, or when your job feels like it is getting on top of you. And exercise is a powerful tool in the quest to reduce stress. However, if you get into that workout with high levels of stress, it will take you longer to recover.

This small but interesting study seems to show that during the hour following a lower body heavy resistance exercise task to failure, students with higher chronic stress scores took longer to recover their maximum strength than their lower stressed colleagues. The lower stressed students had regained 60% of their leg strength after 60 minutes – the more stressed students had regained an average of only 38% of their leg strength at the same measurement point. This effect seemed to hold, even when other possible influences such as fitness, workload and training experience were controlled.

The authors hypothesise that the underlying level of chronic stress pre-workout influences the inflammatory response in the body such that it becomes inadequate to facilitate the repair caused by the acute physiological stress of a tough workout. But the differences are probably due to more than just hormonal control of the inflammatory response. Stress means that we are more likely to sleep worse, eat less optimally and generally not take as good care of ourselves – all these factors can influence how the body heals itself. These are likely to be bi-directional relationships too.

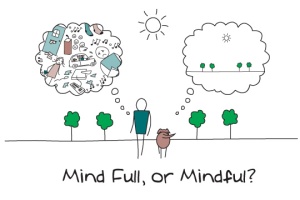

So if you’re stressed and need to workout, you can still go ahead because exercise is an excellent stress-reduction too. But remember, that you’re likely to recover better if you can manage your stress in other ways too before you start to work out. Mindfulness techniques, and focusing on your breathing to influence your parasympathetic nervous system (the part of the nervous system responsible for promoting a calm response) are fantastic ways to bring down the physiological stress indicators in your body. You can see here and here for more tips on that, but here is a simple breathing exercise to try to help bring down your stress levels before you workout:

- Pause for two minutes to just observe your body breathing

- Do this by following your inhalations and exhalations, without trying to control or change anything – just observe

- Focus on feeling the sensations of breathing in the nostrils, the chest and the belly

- If your mind wanders, that’s okay – just return your focus to your breathing

- Practice daily – you’ll get better at it