When I talk about writing, I don’t mean this – blogging – that is, writing in a public way. What I mean is writing privately about things in your life that you are finding stressful and difficult. You know, like keeping a private diary or a journal.

There is an increasing amount of evidence indicating that writing about stressful situations is one of the easiest ways for people to understand circumstances, events, feelings and thoughts that they find themselves returning to in their minds. It may also provide a means to perhaps safely expose themselves to troubling thoughts, that become less troubling as a result of the writing process. Dozens of studies have explored the many psychological and physical benefits for different populations, and the different conditions under which the writing protocol is effective. The protocol itself is pretty simple, and relatively standard. Here are the instructions we gave in a study we did:

“During today’s writing session, we would like you to spend about 10 minutes writing about a traumatic or upsetting experience that has happened to you. The important thing is that you write about your deepest thoughts and feelings. Ideally, whatever you write about should deal with an event or experience that you have not talked with others about in detail.” We asked our participants to do this again on Day 2 and Day 3 of the study too. Of course, not everyone has a traumatic experience, but all of us have had major conflicts or stressors in our lives. That was OK to write about too.

This writing protocol is quite powerful. Time and time again, the results have demonstrated that when people are given the opportunity to write about deeply personal aspects of their lives, they readily do so. It was a very sobering experience being part of the study team in this kind of research. Even though a large number of participants across numerous studies report crying or being pretty upset by the experience, the overwhelming majority reported that the writing experience was valuable and meaningful in their lives.

Although this is a topic area that I have been interested ever since my early postgraduate days (here is a paper that I published on this technique being used out of the laboratory situation, and another early paper here on the potential benefits ), the mechanisms underlying these potential benefits are not well understood. Inhibition was originally proposed as the explanation in early work in the 1980s- that is, the work of not talking about emotional upheaval ultimately led to stress and illness, However, researchers now recognize that this is only part of the picture, and that the effective mechanisms are likely to be more complex and nuanced than this. Not talking about stressful experiences can contribute to social networks being disrupted or breaking down, a decrease in working memory capacity, disturbed sleep, alcohol and drug problems and an increased risk for further stressful events. However, it does seem that expressive writing can help to short-circuit this negative circle.

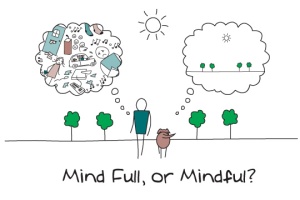

Expressive writing forces people to pause and reevaluate their life story and circumstance. The process of writing also helps to impose a structure beyond mere labeling and acknowledgement of emotions. The act of writing also forces a translation of our thoughts, feelings and images into words – an entirely different representation in the brain, memory, and how we think on a daily basis. All of this may help us to come to a different understanding of our lives, our worlds, and our place in them. As a result of this process, perhaps we begin to talk more, to connect with others differently. Perhaps we come to value the support of others around us. We also see from the research evidence that many unhealthy behaviors start to fall away. Expressive writing also seems to promote sleep and enhance immune function.

Expressive journal writing should not be seen as a cure-all,as the overall effect size for this kind of protocol is modest. We are still not sure about who it works best for, when it should be used, or when other things should be tried instead. The benefits may be slow to come, and may show itself in ways that we don’t yet realize. But it does seem like a promising avenue to research and practice. I have certainly kept a private diary at times in my life when I have been struggling to make sense of things, and I have found it useful. You might too.