It’s true that the way people feel think and decide can be altered by their circumstances. This field of ’embodied cognition’ explores the theory that a person’s physical experiences subtly and unconsciously influence their psychological states. Underpinning this is the notion that the mind is not only connected to the body but that the body influences the mind. In practice, what this means is that our cognition, our representation and understanding of our world is not entirely defined by what is going on in our brains in terms of actual physical activity. Rather, our experiences in the physical world are an important influence. It is also related to the idea that the brain circuits responsible for abstract thinking are closely tied to those circuits that analyze and process sensory experiences received from the body — and its role in how we think and feel about our world.

This approach has important implications. By expanding the resources available to solve a task from simply the brain to include the body and the brain circuits that processes sensory information received perceptual and motor systems, we’ve opened up the possibility that we can solve a task in a very different way than a brain by itself might solve the task. A classic example that is often cited is the baseball outfielder problem where the informational problem of catching the ball is solved by moving in a particular way – a solution that requires both the body and the brain.

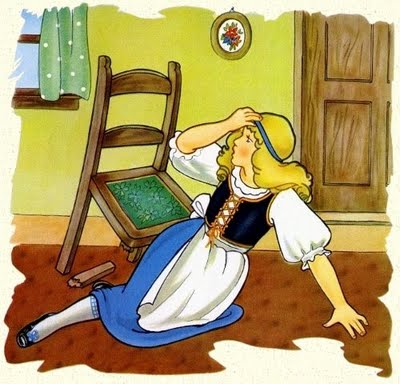

Recently, researchers used an adapted embodied cognition approach to examine whether seemingly unrelated experiences affect individuals’ preferences for stability. Although this study is still in press, a write-up about it can be found here and in a recent edition of The Economist. The researchers split a group in two, assigning one half to a slightly wobbly table and chair, while others had stable furniture. When asked to rate the stability of four celebrity couples, those in the ‘wobbly’ group rated the couple as significantly less stable that the ‘non-wobbly furniture’ group. Moreover, when asked to rate their preferences for traits in potential romantic partners (all participants were romantically unattached), those in the ‘wobbly’ group said that they valued stability in their own relationships more highly to a statistically significant level.

It seems that even a small amount of wobbliness in your physical environment seems to be able to influence the desire for more stable surroundings, including potential partner choice. So the next time you find yourself making seemingly strange decisions that you are having trouble understanding, ask yourself how much you are being affected by the context you find yourself in. And perhaps change your context if you want to experience a different outcome.